Dreams of a Deeper Green

Anjana Janardhan responds to three new artists’ commissions that challenge perceived notions of the UK countryside as a static and exclusive space and propose new ways of reimagining its legacy to include the stories (and bodies) of those rendered invisible over time.

To flick through the pages of a tourist brochure is to encounter a romanticised image of the British countryside – its rolling hills and windswept moors set in aspic – a picture of dignified calm. In Syncopated Green, Arjuna Neuman, pays playful homage to the history of rave culture in Britain and its inextricable relationship to the rural landscape. Divided into three sections, each scored by a different track, the film begins its journey in London’s National Gallery, taking the viewer through the opulent rooms dressed in flocked wallpaper and shiny wooden floors. Constable. Gainsborough. Turner. The camera glides over the surfaces of these paintings in their gilded frames, zooming in on detail after detail in time to the beat. A goat drinking water. A gold-buckled shoe. A farmer ploughing his field. The pale face of an aristocrat dressed in velvet and lace. We leave the calm confines of the museum for the open road as careful brushstrokes are replaced by moving images of grazing cows, cotton clouds and blue skies. Day turns to dusk as a car makes its away down a motorway, headlights on and stereo turned up. The still pastures depicted on canvas become sites of expression, activated by bodies swaying to syncopated rhythms as scenic views give way to muddy fields filled wirth the sight of glistening dancers moving as one. A crumpled flyer. Box-fresh trainers. Glowsticks swaying in the darkness. Found footage from parties – including clips from Mark Leckey’s 1999 video work Fiorucci Made me Hardcore – are overlaid with scenes of the countryside or projected onto the blackened surfaces of handheld mirrors once used by painters to find the so-called ‘picturesque’.

While Neuman reinforces the legacy of dancing bodies within the tranquil landscape, Essi notes conspicuous absences, proposing an alternative vision of the countryside that allows for a broader (and more accurate) story of those who live within it. In Pastoral Malaise, the bucolic English landscape becomes the setting for a re-imagined past. Shot on 16mm and narrated by Jamaican-British actress Angela Wynter, the film’s soft tones, storybook-like imagery and dream-like pacing evoke feelings of nostalgia. Centuries after Constable and Turner set up their easels in search of the sublime, three Black children roam the countryside, playing games and skipping down grassy paths hand-in-hand. Dressed in wool uniforms and knee-high white socks, they blend into the autumnal landscape like figures in a Gainsborough painting – laughing and moving with joyful abandon. Essi intertwines lines from the poem Spring In England written by Jamaican writer Una Marson with the melody of Dorris Henderson’s 1965 cover of British folk song One Morning In May. A prolific writer, feminist and activist and the first Black woman to be employed by the BBC, Marson would eventually return to her native Jamaica where she lived till her death in 1965 – the same year Henderson, a folk singer of African-American and Native American heritage herself – would arrive in England bringing her unique voice to the local music scene. “Take a folk song and sing it back to me in your own way”. In Essi’s hands the rural landscape far from being static becomes a site of potential, brought to life and enriched by the stories of all those who live upon it.

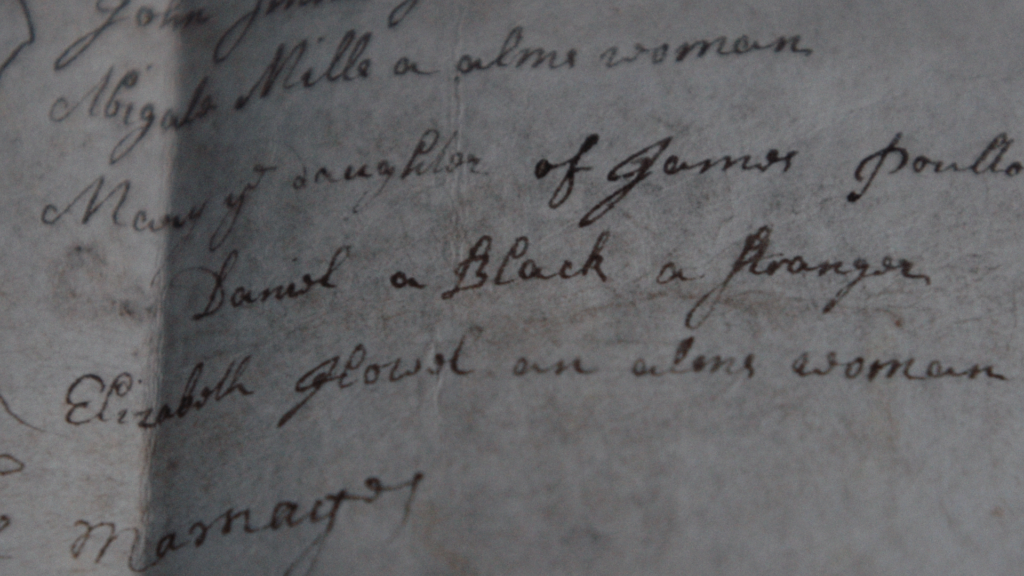

Crowds of dancing bodies may threaten to disturb the peace but a lone body can prove just as conspicuous in a rural setting. In Dan Guthrie’s black strangers, the artist retraces the steps of a man named ‘Daniel’ mentioned in a Bishop’s transcript found in Gloucestershire Archives. Buried in 1719 in Nympsfield on New Year’s Eve, the man is described simply as ‘a black, a stranger’. Intrigued by this discovery and sparse description, Guthrie embarks upon a walk through the local woods in an attempt to recreate this strangers last journey. Extending his hand in friendship, he offers comfortable shoes, water, painkillers and companionable silence. As a Black man walking alone wearing headphones – no bags in his hands or dog by his side – Guthrie notes that his very presence invites suspicion and his appearance perceived as a ‘dark cloud on a distant hilltop’. Assuming a confessional tone, the artist muses on Daniel’s last moments, did he too face such uncomfortable encounters as an outsider to this land? As he reaches into the archive attempting to fill in the gaps, curiosity turns into communion and two lives converge as Guthrie observes he is “Dan walking as Daniel going to find the ‘you in me’ along the way.” The sound of a ticking clock bookends the film marking time and a kinship forged across centuries. Two bodies move in tandem through the forest on a cold December morning as this tender tribute to a forgotten stranger ends in a dazzling display of sound, fire and light.

Anjana Janardhan is a designer and writer based in London. She has contributed to publications including Sight & Sound, BFI and Non-Fiction journal and was selected for New Contemporaries Writing Commissions in 2022. She is a member of the programming team at Open City Documentary Festival.